This blown call shows all you need to know about the state of DC911

DC911 leadership fails to understand that predictable is preventable

Looking for a quality used fire truck? Selling one? Visit our sponsor Command Fire Apparatus

Predictable is preventable. A blown DC911 call on Saturday was so predictable that it illustrates how poor the public safety agency’s leaders are at their jobs. That’s because the same mistake, involving the same street, occurred three weeks earlier and has happened repeatedly during the entire 20-year history of the Office of Unified Communications (OUC).

The truth is that this problem predates OUC and reaches way back to when the Metropolitan Police Department ran 911. This botched address and a series of others just like it keep surfacing at DC911. It occurs with enough frequency that it’s hard to understand why every call-taker, dispatcher, and supervisor aren’t keenly aware of these locations and their problems. It’s even harder to understand why OUC Director Heather McGaffin and her staff appear helpless in preventing these mistakes.

On the surface, Saturday’s error didn’t make waves. No one died. The delay of six minutes wasn’t crucial to the patient’s outcome. There was little muss or fuss heard in the radio transmissions (audio at the top of the page). In fact, a casual listener might have missed the mistake that sent DC Fire and EMS to a bad address.

You also likely won’t read about this error anywhere else. No other news media will cover it, and the city’s political leaders will ignore it. But for STATter911, the error says everything about the poor state of 911 in Washington, DC. The mistake highlights OUC’s inability to handle the basics of its very important mission.

The call

The person injured in a fall on Saturday was at the National Mall, home to our nation’s monuments and museums. Visitors from around the world know it well. But at DC911, the staff has proven they don’t know the Mall well enough to reliably send help.

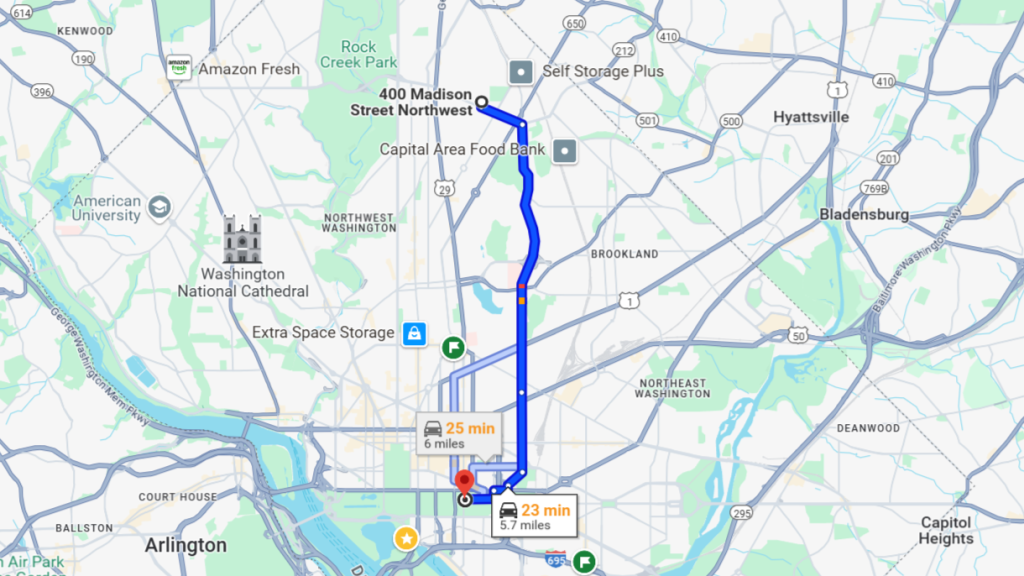

The fall happened on Madison Drive NW, one of two streets running along the Mall from the U.S. Capitol to the Washington Monument. Instead of dispatching the call to the 400 block of Madison Drive NW, firefighters and EMS were sent five miles away to the 400 block of Madison Street NW.

On May 14th, DC911 made the exact same mistake (audio below). It sent DC Fire and EMS to Madison Street NW instead of Madison Drive. In fact, OUC made the mistake twice during the same emergency call. In total, seventeen minutes were lost before the correct dispatch was finally sent to the 900 block of Madison Drive NW. Amid the chaos of those 17 minutes, call-takers, dispatchers, and supervisors ignored a major clue. This call for a sick person came from U.S. Park Police, the law enforcement agency with primary jurisdiction on the National Mall.

The confusion doesn’t just come from the name “Madison”. It also stems from Madison Drive and Madison Street sharing the same hundred blocks between 300 and 1400. There’s also Madison Place NW, across from the White House. It shares the 700 block.

Through the years, there have been many other blown calls involving the Madisons. Same with the two Jeffersons. Jefferson Drive SW runs parallel to Madison Drive along the Mall. It also has a namesake, Jefferson Street NW, with the same hundred blocks.

“Gotchas”

These common mix-ups are what some in 911 call “gotchas.” The “gotchas” are addresses with repeat or similar-sounding names, or other geographical oddities that can lead an unaware 911 worker to send help miles from where it’s needed. Almost every jurisdiction has them. It’s crucial that 911 staff are aware of and always on alert for “gotchas”.

In DC, sound-alikes “Water Street” and “Warder Street”, both in Northwest with similar hundred blocks, are another frequent “gotcha”. Same with Maine Avenue and Main Drive. Florida Avenue in Northwest, which has duplicate intersections with six lettered streets, R to W, has gotten many a call-taker or dispatcher, including just two weeks ago.

STATter911 has written about these “gotchas” frequently over the last six years. On June 22, a veteran dispatcher seemed to ignore the officer of an engine company as he explained three times that there are two intersections, 20 blocks apart in Northwest, where Florida Avenue and R Street meet (audio above). The firefighters were clearly at the wrong one, searching for a car crash. These mistakes happen often enough that you have to wonder if Lexipol’s Gordan Graham’s well-known risk management and public safety concept, “If it’s predictable, it’s preventable,” is something foreign to OUC leadership.

The “gotcha” solutions

I’ve never run a 911 center, but the measures necessary to keep an agency like this from repeating the same mistakes seem pretty obvious.

It starts with initial training. This means excellent geography lessons to include highlighting each of the “gotchas”. It must be clear to 911 recruits and veterans that the expectation is they must learn the “gotchas” so well that alarm bells go off in their heads each time they hear “Madison”, “Jefferson”, “Water”, “Warder”, “Florida”, and the others.

It should become second nature for call-takers to know the techniques for determining which location is the correct one. This might mean asking the caller to spell the street or to find out if they are in Georgetown or near McMillan Reservoir for Water/Warder. It also means paying close attention to the location-determining technology data with the call. Properly using LDT can prevent a call-taker from sending units far away for an injured person on the National Mall. Or it may be as simple as asking the caller if they see the Washington Monument, the U.S. Capitol, or the White House nearby.

Supervisors are the other key to prevention. With OUC’s history of making these mistakes, alarm bells should also sound in the heads of supervisors whenever they see one of these locations pop up on the screen. Supervisors must immediately check that the right location was chosen. Supervisors should also regularly conduct street drills on slower overnight shifts. Those drills should include the “gotchas”.

OUC leadership can also make sure that the dispatch computer has prominent warnings that alert a call-taker whenever one of these “gotcha” street names is entered. This was done for at least some of these locations in 2021 under OUC’s former interim director Cleo Subido. It’s unclear if those warnings are still in the computer.

Then there is accountability, making sure both the call-taker and supervisor share responsibility if these preventable errors continue to occur.

Accountability at the top

OUC’s ineffective leadership is compounded by the failure of the DC Council to conduct effective oversight. Director McGaffin has never been challenged in a council hearing to explain why leadership has been unable to prevent these and other predictable mistakes.

Council member Brooke Pinto, in charge of OUC oversight since McGaffin’s arrival, recently made it easier for the director to avoid accountability. At a hearing a month ago (video above), Pinto said that 40 mistakes STATter911 uncovered this year, including both Madison Drive errors, don’t count. Pinto claimed they aren’t valid since STATter911 doesn’t know the 911 caller’s phone number.

Despite a law to the contrary (that Pinto wrote), she absolved McGaffin of any responsibility to investigate and report address mistakes and other errors submitted to OUC by STATter911. Without STATter911 providing the caller’s phone number, Pinto mistakenly believes that OUC would waste too much time searching for the incident.

With no one conducting serious oversight or holding OUC leadership accountable, it’s easy to see this attitude rolling downhill and being pervasive throughout OUC.

While the concept of predictable is preventable doesn’t seem important at OUC, what does rule the day is a culture of hiding mistakes combined with low expectations. Pinto and McGaffin’s boss, Mayor Muriel Bowser, helped set that very low bar for OUC. It helps justify making the same mistakes over and over, with zero recognition from those in charge that it doesn’t have to be this way.