DC911 sends another National Mall call to a neighborhood 5 miles away

911 center leaders continue to show they’re not up to the job

Looking for a quality used fire truck? Selling one? Visit our sponsor Command Fire Apparatus

One month ago, STATter911 posted a column titled “This blown call shows all you need to know about the state of DC911.” It used a single 911 call as a window into the 911 center’s poor training standards and inability to handle the basics of this crucial job. STATter911 showed that the same location, amid some of the most visited tourist attractions in Washington, was wrongly dispatched multiple times this year and has been a source of confusion for poorly trained call-takers, dispatchers, and supervisors for many years. A month later, the problem continues. STATter911 knows this because on Saturday, DC911 sent a call intended for a teenager having trouble breathing along the National Mall to the same wrong neighborhood five miles away where previous blown calls were dispatched.

In this case (radio traffic above), DC Fire & EMS Department crews were dispatched to 14th Street and Madison Street NW. That’s in the northern part of the city. Emergency help wasn’t needed there. It was needed at 14th Street and Madison Drive NW, in the center of the city. The intersection is flanked by the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. It’s in the shadow of the Washington Monument, a little more than a block away. Hundreds of thousands of visitors to the nation’s capital know and recognize this spot. Somehow, too many working at DC’s Office of Unified Communications don’t.

Even though the confusion between Madison Drive and Madison Street has long been a source of trouble at DC911, not one call-taker, call-taker supervisor, fire/EMS dispatcher, or fire/EMS dispatch supervisor bothered to check if the agency got it right this time. It took an apparently suspicious DC Fire & EMS Department officer, working miles away in the separate Fire Operations Center, to double-check the call and alert DC911 dispatchers that, once again, they blew it. That occurred two minutes into the response. Even that wasn’t enough for OUC to fix the problem. The dispatcher didn’t immediately recognize that the units they had assigned to the call were miles away, and that crews much closer to Madison Drive should be sent. It took almost five additional minutes before the problem was corrected, and closer units were dispatched to the right location.

This same Madison Drive and Madison Street mistake occurred on July 5th, and twice on May 14th. Those are just ones STATter911 discovered this year. There could be more. STATter911 has documented this problem for about six years. As we wrote in July, it’s not just the Madisons. There are other addresses that have a long history of being confused with locations in other parts of the city. Almost every jurisdiction has a version of this problem. Some 911 centers refer to them as “gotchas”.

Effective 911 leaders know that their job is to ensure that staff recognizes and drills on these “gotchas”. There should be warnings about each location in the dispatch computer. The goal is to have alarm bells ring in the heads of 911 workers each time a call is received for one of these addresses, so that extra care is taken to send help to the right spot. The July column outlined common-sense steps 911 centers can take to make this happen.

The problem is that OUC Director Heather McGaffin appears to be incapable of instilling these skills in her staff and ensuring they can handle the basics of working in a big city 911 center. The frequent mistakes that occurred when McGaffin began running OUC in January 2023 still happen.

What McGaffin has proven to be good at is hiding DC911’s errors and putting on dog and pony shows to divert attention. Last week, McGaffin, OUC leadership, and call-takers – about 40 people from the agency – were on duty at the Baltimore Convention Center. As part of an industry convention, APCO 2025, they were demonstrating OUC’s remote call-taking center. It’s intended as a backup call-answering site. The agency reports the workers handled about 100 911 calls amd 200 311 calls rerouted to Baltimore from DC. During that time, 2000 people walked through the mobile 911 center (OUC video below).

Also at DC911 last week, a dispatcher in Washington failed to recognize that a fire truck crew was in the middle of a very serious emergency. It took three radio transmissions over two minutes and 30 seconds before the dispatcher acknowledged Truck 13 had driven into a gun battle. It was later found that two bullets pierced the cab of the ladder truck. Earlier this year, a paramedic assaulted by a patient waited for 15 minutes for DC Police to answer the urgent call for help. In case you’re not aware, there is a long-standing lack of trust by firefighters, medics, and EMTs that DC911 will get them help when it’s most needed.

What makes all these DC911 problems worse is the complete lack of effective oversight by the DC Council. Council member Brooke Pinto has the job of holding McGaffin accountable on things like repeated address errors and promptly responding to urgent situations. Unfortunately, Pinto has made it clear she has no interest in that role.

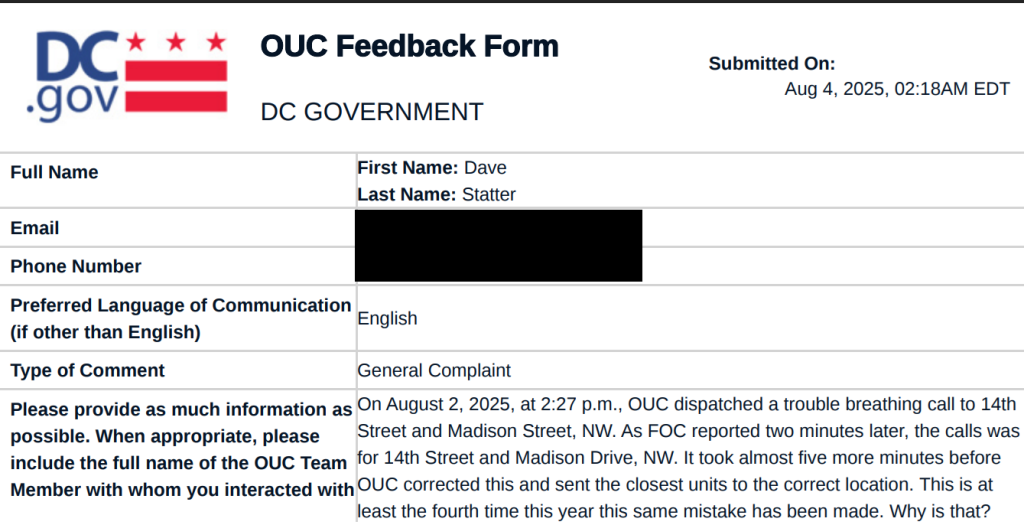

During a June budget hearing (above), Pinto said she won’t be looking into the four failures to dispatch EMS to the National Mall, or dozens of other errors uncovered by STATter911 this year. She indicated that 40 documented address and other problems reported to both OUC and the council member’s office will be ignored. That’s because STATter911 didn’t include the 911 caller’s phone number in the OUC Feedback Form. Of course, the caller’s number is not normally available to STATter911. McGaffin closely guards the release of all 911 call information, considering it “private”. Pinto erroneously believes, based on information she says she got from OUC, that it’s too challenging and time-consuming for OUC to investigate a call without the phone number.

Not one of those official OUC Feedback Forms is reflected, as required by law, in monthly OUC public reports of address and other errors. Pinto’s failure isn’t just about STATter911’s reporting. Most of the same calls cited by STATter911 were also reported to OUC by DC Fire & EMS through the staff of the previously mentioned Fire Operations Center. Those also aren’t reflected in the monthly reports. In fact, OUC wants us to believe that for all of 2025, covering about a million 911 calls, there have been only two address mistakes, and neither was the fault of 911 workers.

In summation, here are the recent takeaways to help you understand 911 in the nation’s capital:

- DC911 can receive its 911 calls 40-miles away in Baltimore, but it regularly can’t dispatch emergency help to the National Mall or promptly send help to firefighters under attack.

- The OUC director, who refuses FOIA requests for even the most basic information about 911 calls, apparently allowed 2000 strangers to listen in and view that same “private” information.

- The council member who wrote the law requiring OUC to report 911 errors each month is helping DC911 break the law.

All of this makes perfect sense. Right?